It was 1962 in Barbados. One moment he was batting. The next he was on the ground with blood coming from his nose and ears. That one ball from Charlie Griffith did not just end his innings. It ended his Test career. It nearly ended his life.

Born on a Train, Made for a Fight

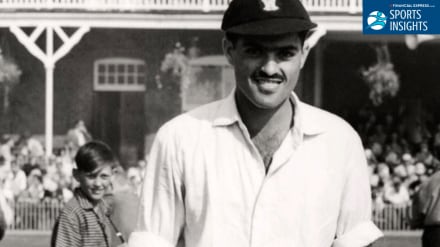

Nari Contractor entered this world in an unusual way. His mother was travelling on a train from Dahod to Bombay. The driver was her own brother. When labour started, the driver stopped the train at Godhra station. That is where Nari was born.

That simple fact of birth gave him something important. He could play for Gujarat in Indian domestic cricket. And play he did. On his first-class debut he did what very few have ever done. He scored two centuries in the same match. He became only the second batsman in history to achieve this.

People in Indian cricket soon noticed something about Contractor. He was tough. Genuinely tough. At Lord’s he batted with a broken rib. He scored 81 runs while his entire team managed only 168. That kind of grit made him the youngest captain of India at that time. The country thought they had found a leader for the future.

Caribbean Warning in a Cocktail Party

The 1961-62 tour of West Indies started badly for India. They lost the first two Tests by huge margins. Contractor’s own form had deserted him. He had managed only 26 runs in four innings. The team was struggling.

After the second Test defeat at Sabina Park, they travelled to Barbados for a tour match. The opposition had a pace attack that terrified batsmen worldwide. Charlie Griffith, Wes Hall, and George Rock. These men were fast and they were hostile.

Before the match, Contractor attended a cocktail party. Frank Worrell, the West Indies captain, took him aside. Worrell gave him a serious warning. He said the West Indies fast bowlers were injuring players regularly. He specifically mentioned Griffith. Worrell told Contractor how Griffith had once hit an 18-year-old batsman on the head without even saying sorry. He advised Contractor to avoid getting hit at all costs.

Contractor never wanted to play that match, he had actually planned to sit it out entirely. But with injuries decimating the Indian team, he found himself with no way out. He simply had to take the field.

The Charlie Griffith Delivery: 60 Seconds That Changed Indian Cricket

Barbados won the toss and scored 394 runs. India began their reply shortly before lunch on day two. Contractor and Dilip Sardesai opened the batting. Griffith bowled one over before lunch. He did not seem that dangerous. As they walked back to the pavilion, Sardesai smiled at Contractor and said, “Fast, my foot.” They felt relieved.

After lunch, everything changed. Hall dismissed Sardesai for zero in the first over. Rusi Surti came in to bat. Griffith took the ball again.

The first ball of Griffith’s over was short and flew past Contractor’s face. Surti immediately shouted that Griffith was chucking. Contractor told him to tell the umpire if he felt that way. The next two balls were equally quick. Off the fourth ball, Contractor almost got out at short leg while trying to defend.

Then came the fifth ball. People still argue about what kind of delivery it was. Some say it was a proper bouncer. Others say it was just short of a length. What is certain is that Contractor misjudged it completely.

According to Wisden, the most trusted voice in cricket, “Contractor didn’t duck into the ball. He got behind it to play. He probably wanted to fend it away towards short-leg, but couldn’t judge the height to which it would fly, bent back from the waist in a desperate, split-second attempt to avoid it and was hit above the right ear.”

The ball struck him. He collapsed immediately. Blood started flowing from his nose and ears. Ghulam Ahmed, the Indian team manager, ran onto the field and helped him walk off.

Blood on the Pitch and a Hospital Fight

Contractor changed his bloodstained clothes in the dressing room. But the bleeding would not stop. He was rushed to hospital immediately.

While he was fighting for his life, the match continued. Vijay Manjrekar came in to bat. Griffith hit him on the nose too. The bowling was simply too fast and too dangerous for that era.

At the hospital, Contractor’s condition got worse quickly. He started vomiting. The left side of his body stopped moving properly. Ahmed had to make an emergency decision. He authorized an immediate operation.

The local surgeon was not a brain specialist. The neurosurgeon was in Trinidad and would not arrive until next morning. But they had no choice. The surgeon did what he could. He relieved the pressure on Contractor’s brain. That operation saved Contractor’s life. It bought him enough time for the proper neurosurgeon to take over the next day.

Several players donated blood to keep Contractor alive. Frank Worrell, the West Indies captain who had warned him, gave his blood. So did Chandu Borde, Bapu Nadkarni, and Polly Umrigar. The opposition captain giving blood to save an Indian batsman. That gesture said everything about cricket in that era.

Borde remembered the terror of that first operation. “The lights went off as the operation was going on. We thought that was a bad omen. It took three to four hours. That was miserable.”

Charlie Griffith himself visited the hospital after play ended. He was shaken. The players only then understood how serious the situation was.

No Complaints, Only Facts

It took Contractor six days to regain full consciousness. His wife flew in from India to be with him. Before leaving Barbados, Contractor told her something remarkable. He said it was not Charlie’s fault. It was his own fault.

Later in life, Contractor explained his thinking. “Those were days when there were no helmets, no restriction on the number of bouncers in an over and no restrictions on beamers either. The pitches were uncovered. But it was the same for everyone then and we were prepared for the challenge. No complaints.”

Think about that. No helmets. No rules about how many bouncers a bowler could send down. No protection against beamers. Uncovered pitches that got faster and more dangerous as they dried. Every batsman faced the same risks. Contractor accepted his fate without bitterness.

Comeback That Never Came

The medical advice was clear. Contractor should retire from Test cricket. The head injury was too serious. But Contractor was a fighter. After ten months away from the game, he came back to first-class cricket. He scored runs again. He proved he could still bat.

But the Indian selectors never picked him again. They were too afraid. What if he got hit again? What if next time the result was worse? They could not take that responsibility.

So Contractor kept playing domestic cricket. He played for Gujarat until 1971. In his last first-class game, he scored 93 runs. He left the game on his own terms, but he never wore the India cap again after that tour of West Indies.

Human Cost of a Game

Nari Contractor lived. He is alive even today, in his Nineties. But that cricket ball in Barbados took something from him. It took his international career. It took his place in Indian cricket history as a long-serving captain. It gave him instead a story of survival and grace.

Frank Worrell’s warning had been real. His blood donation had been genuine. Charlie Griffith’s bowling had been ferocious but within the laws of that time. Contractor’s acceptance had been noble. The selectors’ fear had been understandable.

This is not a story about blame. It is a story about how a simple game can become something else in a split second. How a ball made of leather and cork can change a man’s life forever. How sometimes the bravest thing is not to fight on, but to accept what has happened and move forward without hatred.

Nari Contractor did that. He batted on in domestic cricket. He lived his life. He never complained. And in doing so, he showed a kind of courage that matters more than any century or any captaincy.