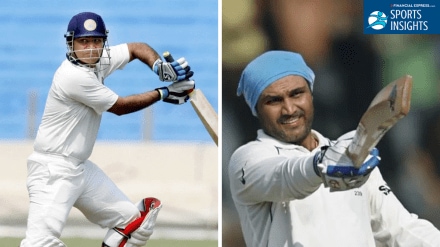

Mumbai’s Brabourne Stadium smelled of sea salt and possibility on December 2, 2009. India needed a win against Sri Lanka to grab the number one Test ranking for the first time ever. Virender Sehwag walked out with a back so stiff he could barely tie his shoelaces that morning. By sunset, he stood 284 not out and the cricket world stood still.

When Pain Met Purpose

On most mornings, teams stretch, warm up, and prepare for a long grind. India that day walked out thinking, alright, let’s survive a bit. Sri Lanka had made 393. The ball was turning for Indian spinners. Murali was glaring with his usual intensity. Everything suggested a standard slow Test match.

Sehwag’s back was killing him. The physiotherapist worked on it for an hour before play started. Conventional wisdom said India should play safe and steady. Sehwag heard that advice and set it on fire.

He started slowly by his standards. The first twenty runs took some time. Then something clicked. He leaned into his bat between overs, grimacing. He fell over while playing shots, got up slowly. The pain was real and visible. It didn’t matter. He kept hitting. The back spasm became a background detail, like traffic noise you stop hearing after a while.

Sri Lankan bowlers tried everything. They set defensive fields with men on the boundary. Sehwag stepped out and chipped over extra cover. They packed the leg side. He reverse-swept past point. They bowled wide outside off stump. He flicked behind square. They bowled outside leg stump. He inside-out drove through cover. Each tactic died a quick death.

Sehwag vs Murali: Dismantling the Greatest Off Spinner of All Time

Muttiah Muralitharan was the greatest off-spinner ever. He had 800 Test wickets. That afternoon he looked like a club bowler who had wandered into the wrong match. Sehwag took 78 runs from the 70 balls Murali bowled to him. That’s almost eleven runs per over. Against Murali.

The most telling moment came when Sehwag was on 248. Murali tossed up a doosra, his mystery ball that had fooled batsmen for two decades. Sehwag read it off the hand, went deep in his crease, and paddle-swept it fine for four. Murali’s shoulders sagged. He looked away. He said something to Sehwag, who just smiled. That smile said everything. He had solved a puzzle that entire generations couldn’t.

The Silent Helpers at the Other End

Murali Vijay played his role perfectly. He rotated strike, giving Sehwag the lion’s share of bowling. He attacked when needed, showing he wasn’t just a passenger. His 87 was forgotten in the Sehwag storm but it was crucial. It allowed Sehwag to breathe between assaults.

Rahul Dravid, at the other end, looked like a monk meditating while a festival exploded next door. While Sehwag exploded, Dravid played classic cover drives and defended with that straight bat of his. He made 62 and never once tried to match Sehwag’s tempo. He understood his job was to hold one end and watch the master at work. The partnership added 237 runs. Dravid’s experience helped Sehwag pace himself through the back pain.

Numbers That Look Like Typos

Let’s talk numbers because they tell a story no words can match. Sehwag faced 254 balls. He hit 40 fours and 7 sixes. That’s 202 runs in boundaries alone. He scored at a strike rate of 115. That happened in a Test match, not a T20 carnival.

He went from 100 to 150 in just 30 balls. The longest he went without hitting a boundary was 12 deliveries. Think about that. In five hours of batting, he never had a dry spell longer than two overs.

It wasn’t just runs. It was speed. India piled 726. They won by an innings. And they did it because Sehwag erased the need to play Test cricket at Test pace.

That day he became the fastest maker of multiple double centuries for India. He broke his own record for most runs in a day by an Indian. He almost became the only batter to make three triple centuries. And he pushed India into a position where the Test ranking tables began to wobble towards a historic shift.

India had never been No.1.

This innings was one of the blocks that built that rise.

Seven Runs Short of Immortality

The third morning started with Brabourne buzzing. People had skipped work. School kids had fake medical certificates. Everyone wanted to see history – the first man with three triple centuries. Sehwag needed 16 runs to reach 300

He added nine runs that morning. In the fourth over, he chipped a simple return catch back to Murali. The ball went straight to the bowler’s hands at waist height. Sehwag stood there for a second, showing rare anger. Then he smiled, raised his bat, and walked off. The crowd stood and cheered for five minutes.

He had made 293. Seven runs short of 300. It didn’t seem to bother him much. In the dressing room, he was laughing within minutes. His logic was simple – he played each ball as it came, and that one was there to be hit. He just hit it to the wrong person.

Why This Day Still Matters in 2025

Sixteen years later, cricket has changed. Batsmen score faster in Tests now. But Sehwag’s 293 remains special because of the context. This wasn’t a flat track against a weak attack. This was a proper Test match with championship implications.

His 2009 numbers look fake even today – 70 average at 109 strike rate in Tests. In 2010, he made 1422 runs at 62 average and 91 strike rate. Modern ODI players would kill for those numbers. In Tests, they are from another planet.

The innings taught a generation that Test cricket could be fun. That you could dominate world-class bowling without boring people to death. That a five-day game could have moments as exciting as any T20 finish.

The fans who missed that day at Churchgate still talk about it in Mumbai’s local trains. Those who were there tell their children about it. It was more than cricket. It was watching a man turn pain into poetry, bowlers into spectators, and a game into a memory that still gives goosebumps sixteen years later.

In the end, Sehwag didn’t need that triple century to become immortal. He already was. The numbers were just proof.