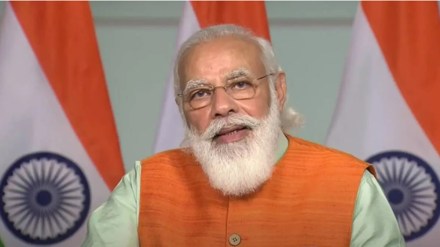

In July, prime minister Narendra Modi warned the nation about the evils of ‘revdi’ politics while inaugurating the Bundelkhand Expressway. Last Sunday, after inaugurating `75,000 crore of infrastructure projects in Maharashtra, he said political leaders who use the “hard-earned money of taxpayers” for “shortcuts” are the “biggest enemy” of the taxpayers. The prime minister was obviously trying to showcase his government’s expenditure on infrastructure in stark contrast to the populist schemes adopted by some of the state governments, to make the point that the politics of “half income and full expenditure” must be discarded in favour of “sustainable solutions”.

Modi’s red-flagging of “shortcuts” comes just days after the Congress’s narrow victory in the Himachal Pradesh assembly elections, in the run-up to which the party had promised to bring back the old pension system, 300 units of free power, and a basic income for women aged 18-60 years. The state’s finances, though, show that such largesse can’t be sustained in a fiscally responsible manner. Himachal’s total outstanding debt, as a percentage of its gross state domestic product (GSDP), has risen to 43%, which is well above the 15th Financial Commission’s target of 36%. The state’s own revenue is just 31%, which means it is largely dependent on central transfers.

Also read: India lessons for the G-20

Indeed, in state after state, parties have made fiscally-irresponsible promises of “freebies”, and this has paid electorally for most. In Punjab, where the total outstanding debt is a whopping 53.3% of the gross state domestic product, the Aam Aadmi Party which was voted into power earlier this year had promised freebies wide and deep. Indeed, while Modi is justifiably concerned about the erosion of the state’s capacity for “sustainable solutions” because of competitive populism, his own party hasn’t shied away from it in the past. The Uttar Pradesh unit of the BJP had promised state-level farm-loan waivers in 2017, which set off a cascade of similar promises by other states, resulting in a whopping `2 trillion of loan-waivers announced. And, in Himachal, it promised free tablets, monthly data, scooters/bicycles, LPG cylinders and what not.

Also read: Explainer: Can the CBDC be anonymous?

The Supreme Court had directed the Centre to consult the Finance Commission on regulating “irrational freebies”. A welfare push from the government in key areas—crucially, at key points of time—must not be resisted. For instance, the Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana likely saw millions of families through the worst of economic pain wrought by the pandemic, but should it have continued as long as it has? Even a MGNREGA, which the present dispensation at the Centre had disparaged as “a monument to the UPA’s failure”, has provided much needed income relief to the rural poor. But, carrots for the electorate in the form of reverting to the old pension scheme, or basic income to women across economic classes surely call for some form of accountability. Beyond the locking of political horns, however, Modi’s warning against fiscally profligate policies, which tend to be driven more by electoral concerns, echoes widespread concerns over “wasteful” spending. At the very least, the states and the Centre must work towards consensually arriving at some new form of financing in the Inter-State Council. Former revenue secretary Tarun Bajaj has recently made a case for taxing agricultural income above a certain threshold. Though the wisdom dawned on him only after his retirement, it would be interesting to see whether the government can muster enough courage to phase out this “freebie”.