By Raju Mansukhani

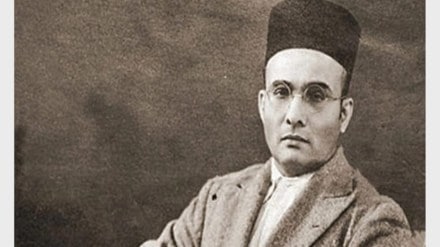

He gave us ‘The Indian War of Independence – 1857’. It was 1907 and a young 24-year-old Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was living and studying in London, networking with exiled revolutionaries in Paris and writing his heart out for a book that made history across continents when it was completed by 1909.

Savarkar was conscious of time and anniversaries: marking fifty years after 1857 and the Queen’s Proclamation that followed in 1858. From May 9 to May 13, 1857 witnessed the fires of revolt, rebellion, mutiny, and independence being lit, setting ablaze east, north, and central India.

In ‘The Indian War of Independence – 1857’ Savarkar builds an ideological bridge to 1757, to the battle of Plassey which marked the beginning of the British East India Company’s rise to power.

Hence for him in London in 1909, the ignominy of Plassey in 1757 was as alive and vibrant as was the valour and revolutionary war of 1857. It was in this die-hard spirit of patriotism, with a passionate love for the Motherland and the crusading call of a revolutionary that he wrote his voluminous work. It was written in Marathi and was titled Atthharahasau Sattavanche Swatantrya Samar.

As we dig into its English edition, Savarkar’s introduction sets the pace and tone: “I found to my great surprise the brilliance of a War of Independence shining in “the mutiny of 1857.” His words sparkle with the clarity of a crusader. “The spirits of the dead seemed hallowed by martyrdom, and out of the heap of ashes appeared forth sparks of a fiery inspiration.” Adding more intensity to his poetic burst, he wrote that the nation that has no consciousness of its past has no future.

Such prophetic thoughts from a young revolutionary do take the reader by surprise. The past of a nation was to be claimed and reaffirmed, but as Savarkar wrote, “how to use it for the furtherance of its future. The nation ought to be the master and not the slave of its own history.”

Living in harsh colonial times, often pursued by British intelligence agencies, facing up to their supremacist attitudes and hatred for natives, Savarkar shared timeless words of advice: “It is absolutely unwise to try to do certain things now irrespective of special considerations, simply because they had been once acted in the past. The feeling of hatred against the Mahomedans was just and necessary in the times of Shivaji but, such a feeling would be unjust and foolish if nursed now, simply because it was the dominant feeling of the Hindus then.”

To be paying tributes in the 21st century to this landmark publication and its young firebrand author, it is befitting to also salute a cast of patriotic characters without whose guidance and support ‘The Indian War of Independence – 1857’ may not have seen the light of day.

There was Shyamji Krishna Varma with whom Savarkar learnt how to organise young Indian revolutionaries scattered in different countries though many were living in UK. When Shyamji Krishna established an ‘India House’ in London, it emerged as a veritable training ground and hostel for several revolutionaries: each one more idealistic, and patriotic than the other, leading dramatic dangerous lives away from their homeland.

Other revolutionaries included Madanlal Dhingra, Bhikaji Rustom Cama, whom the world remembers as Madam Cama. In Paris or in London, Madam Cama, along with Sardar Singh Raoji Rana, used to struggle arms to Indian revolutionaries at home and gave training in firearms.

At the India Office Library, Savarkar spent months studying historical accounts of the 18th and 19th centuries, comprehending the process of systemic exploitation and ruthless subjugation of the sub-continent by British East India Company and their armies.

His reading list included John W Kaye’s ‘A History of the Sepoy War in India, 1857-58’ published in three volumes between 1864 and 1876, and George B Malleson who contributed to Kaye’s work with ‘History of the Indian Mutiny’; later these official histories became a six-volume set titled, ‘Kaye’s and Malleson’s History of the Indian Mutiny’.

Besides, he ploughed through the accounts of officers and administrators like Charles Ball, Dr Alexander Duff, Sir JH Grant, Holmes, and Thomas Lowe, to name just a few. Utilising military and State documents made available to them each account was reinforcing the official colonial line: 1857 was essentially a military mutiny. Long-term recruitment policies of the native sipahis and then their opposition to greased cartridges were the incendiary reasons why the mutiny occurred.

As Prof Amar Farooqui, in his latest book ‘The Colonial Subjugation of India’ writes, “the foundations of colonial historiography on the revolt were laid by the immensely influential work of John W Kaye, who was a colonial official and a military historian.”

Savarkar’s critique of the British historians and authors was spot-on; he termed their writing as most extraordinary, misleading, and unjust about the Revolutionary War. “Most of them have written history in a wicked and partial spirit. Their prejudiced eye could not or would not see the root principle of that Revolution,” he said, questioning in the pages of the book: “Is it possible, can any sane man maintain, that all-embracing Revolution could have taken place without a principle to move it? Could that vast tidal wave from Peshawar to Calcutta have risen in flood without a fixed intention of drowning something by means of its force? Could it be possible that the sieges of Delhi, the massacres of Cawnpore, the banner of the Empire, heroes dying for it, could it ever be possible that such noble and inspiring deeds have happened without a noble and inspiring end?”

Modern-day readers may not be aware of the influence of the Italian nationalist-thinker Guiseppe Mazzini over Vinayak Savarkar, who had translated important texts of Mazzini into Marathi back in 1906. Mazzini’s views on nation, nationhood, nationalism, and republicanism were building blocks of Savarkar’s ideas as he plunged into one of the bloodiest, gory chapters of British colonial history.

“Mazzini had said that every revolution must have had a fundamental principle. Revolution is a complete rearrangement in the life of historic man. A revolutionary movement cannot be based on a flimsy and momentary grievance,” wrote Savarkar, referring to the relatively minor factors such as disaffection among the military and the use of newly-introduced greased cartridges.

He felt it is always due to some all-moving principle for which “hundreds and thousands of men fight, before which thrones totter, crowns are destroyed and created, existing ideals are shattered and new ideals break forth, and for the sake of which vast masses of people think lightly of shedding sacred human blood.” Savarkar searched for the prime motive of the history of the tremendous Revolution that was enacted in India through 1857 to 1858.

Through passion-filled questions, which may seem rhetorical when read in a historical account, Savarkar demonstrated a youthful challenge to the British historical narrative which had overwhelmed the colonial world and been accepted as the gospel truth.

“What, then, were the real causes and motives of this Revolution?” asked Savarkar. “What were they that they would make thousands of heroes un-sheath their swords and flash them on the battlefield? What were they that they had the power to brighten up pale and rusty crowns and raise from the dust-abased flags? What were they that for them men by the thousand willingly poured their blood year after year? What were they that Moulvies preached them, learned Brahmins blessed them, that for their success prayers went up to Heaven from the mosques of Delhi and the temples of Benares?”

Savarkar identified the causes and motives as the great principles of ‘Swadharma and Swaraj’. Swadharma means ‘one’s own religion or dharma’. The Bhagavad Gita emphasises the importance of lawful conduct of oneself, according to one’s religion and abilities. Swaraj refers to self-rule, self-government and its roots may be traced to Vedic concepts of self-governance. Swaraj later became the rallying cry of the Indian national movement.

For Savarkar, as he read and researched the early 19th century and how the entire sub-continent had come under the sway of the British East India Company’s raj, it was religion which was in peril, in danger. He wrote, “In the thundering roar of ‘Din, Din,’ which rose to protect religion, when there were evident signs of a cunning, dangerous, and destructive attack on religion dearer than life, and in the terrific blows dealt at the chain of slavery with the holy desire of acquiring Swaraj, when it was evident that chains of political slavery had been put round them and their God-given liberty wrested away by subtle tricks—in these two, lies the root-principle of the Revolutionary War.”

He was deeply conscious of the role of history, historical personalities and the collective imagination of millions of people. His words, brimming with fire, “In what other history is the principle of love of one’s religion and love of one’s country manifested more nobly than in ours? However much foreign and partial historians might have tried to paint our glorious land in dark colours, so long as the name of Chitore has not been erased from the pages of our history, so long as the names of Pratapaditya and Guru Govind Singh are there, so long the principles of Swadharma and Swaraj will be embedded in the bone and marrow of all the sons of Hindusthan! They might be darkened for a time by the mist of slavery—even the sun has its clouds —but very soon the strong light of these self-same principles pierces through the mist and chases it away.”

‘The Indian War of Independence – 1857’ is a voluminous work, running over 550 pages in its English edition. Savarkar, through its four parts titled ‘The Volcano’, ‘The Eruption’, ‘The Conflagration’ and ‘Temporary Pacification’, effectively challenged and convincingly changed the colonial narrative when he highlighted and explained, “Never before were there such a number of causes for the universal spreading of these traditional and noble principles as there were in 1857. These particular reasons revived most wonderfully the slightly unconscious feelings of Hindusthan, and the people began to prepare for the fight for Swadharma and Swaraj.”

Even before ‘The Indian War of Independence – 1857’ was completed in 1909, its entry into India was banned by the Government before its publication could be organized! The ban was finally lifted by the Congress Government of Bombay in May 1946; now the first authorised edition of the book saw the light of day in India. According to a publisher’s note of 1947 tracing the history of the book itself is a dramatic chapter of India’s freedom struggle.

(The author is a researcher-writer on history and heritage issues; a former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya.)

(Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of Financial Express Online. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.)