In the summer of 2015 at the French Riviera, Neeraj Ghaywan stood on the stage at the famous Debussy Theatre venue of the Cannes Film Festival receiving the Promising Future Prize for his debut film, Masaan, an anti-caste drama set in the holy city of Varanasi. Now, exactly a decade later, the Mumbai-based filmmaker is chasing Oscar glory with his sophomore feature, Homebound, set in the Hindi heartland and probing the catastrophic impact of caste and social prejudices on the young people. Continuing its dream run on the international film festival circuit following the world premiere in Cannes, Homebound, India’s official entry to the Best International Feature Film Oscar Award, drew a huge audience at the 22nd Marrakech International Film Festival (November 28-December 6) in Morocco where it was part of the event’s gala presentation programme.

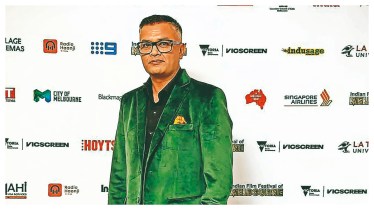

Ghaywan talked with Faizal Khan at the Marrakech film festival about the remarkable response to Indian films at major international film festivals abroad today, the new generation of filmmakers across the country who are not afraid to take on taboo subjects, and the Oscar campaign for Homebound, among others. Excerpts from an interview:

Q: In recent years in Indian cinema, we are witnessing the new generation of Indian filmmakers who are not afraid to take on taboo subjects like the anti-caste topic in both your films, Masaan and Homebound. Your comment.

I think we are moving away from talking about people who are often not seen, not heard. We’re talking about mostly in our cinema at least, in Hindi cinema, about people who are mostly the urban population, or the upper caste population. But nobody’s talking about the stories, of things that matter, like jobs. I thought through this and it’s not like I want to make all these political films. It’s just that I feel like somewhere it feels like you want to… I’m drawn towards these stories mostly because of, maybe, my socialist background or like from the community that I belong to.

So I’m navigated more towards stories that involve talking about people from the marginalised communities. My issue is that whenever we talk about them, we talk about them in statistics. It’s easier to talk about it that way because then you don’t have the guilt. So the idea is to pick people and see the human story behind it, see the human behind it. Not just from a victimhood lens, but also see it from a completely humanitarian or a human angle, which also involves a lot of joy and laughter and, you know, interpersonal relationship, familial relationships. So that is the intent, and also to answer this big question about like, why do migrants leave? You know, that is a big question that we all want to know, and this is also a film too, in an attempt to find that out.

Q: Homebound had a theatrical release in India and has been screened at major international film festivals abroad. How important are these two audience, at home and abroad, for the film?

I’ve seen that the audience reactions across the festivals and in India have been the same. You can hear the collective sobs in the theatre both in India and abroad. People come to me, they’re crying, they hold my hand, and they say, thank you for making this film. I think people connect with it because it talks about a universal theme of connection as a form of resistance. And that’s why I think it moves people. And the angle about the coronavirus pandemic. I think everybody around the world remembers where they were during that time.

We all want to immediately forget about it and also not forget about it. I think it offers a sort of a catharsis to all of us in the sense that you realise what is that went down. And maybe we all were privileged in our homes, you know, making banana bread, pizza, and talking about how we have to clean our house while in the rest of India, there was another reality that we were only seeing in the newspapers. But we only saw through media, and again, as numbers, not as a human story as to see why did they (migrants) leave their workplaces, what happened to them? All of these things, really connected well with the audience and people around the world, who are not seen and heard, and they feel validated seeing it, and also people who come from privilege, when they see it, they realise their privilege and they feel so guilty about, like, not paying back to society.

Q: As a filmmaker you probe social prejudices through the lives of young people. How important it is for you as an artist to respond to these prejudices and show a way forward in the future?

It’s essential to talk about what the youth are going through. I’m not talking about the big issues, but I’m talking about the micro-aggressions, the little things that people say and do to people, thinking that they won’t feel anything. But how it breaks their spirit, how it breaks the human inside of them, and how a lot of life decisions are made on the basis of the last name, the background, which I personally have gone through in my life.

Even with Mohammed Shoaib Ali’s character (played by Ishaan Khatter) in the film, it’s like people think that it’s okay to make fun of him during an India-Pakistan cricket match. Even at workplaces, how it dehumanises someone, and how they make their life choices dependent on that, and how it also is sort of making them leave their homes and find places where they want to be. They want to be seen, at the same time they want to be invisibilised, you know, this gig economy or being a worker in a factory, so that they just could earn and get that respect and get their house built.

Q: Masaan was an entirely independent film while Homebound has a big production house, Dharma Productions of Karan Johar, behind it. How different were the productions processes for both movies?

I find it even more empowered. Because such a big studio, making an independent-minded film with such themes is something to be praised about. And I can’t thank Karan Johar enough because he has been a rock to this film. He has been through and through at every stage. He read the script and he has always wanted to work with me. He said, ‘I want to make a film like yours, and I don’t want to get involved in any way. I only want to empower you.’ And so, once he read the script, he just saw only the final cut of the film. Every single freedom that was given to me was like, you do you. And that, with the combination of (American filmmaker) Mr Martin Scorsese joining in (as executive producer and mentor) was a very big, a new thing. We’ve not seen a studio come on board with these actors who are popular. I’m making an independent film, which is sort of festival-oriented. And Mr Scorsese is lending his name. This sort of thing certainly, I guess, hasn’t happened before, and it means a lot for our Indian cinema as well.

Q: After Masaan in 2015, it took ten years for Homebound, your sophomore feature.

It’s just that I want to make something that aligns well with who I am, with my world view, and how it makes me connect with the rest of India, the India that has not been seen. I just want to tell those stories, and I was trying to find something that says this, and this was it. I totally jumped towards it. I did make a lot of TV shows and commercials in the last decade and of all those I’ve done in the middle this felt like the one that is totally my calling.

Q: Homebound is a gala presentation in Africa, which shares the same concerns and challenges like in India in terms of migrants, refugees and social issues.

I feel there is more relatability because of the apartheid and other social issues that this continent has gone through. The film was screened at the Cairo International Film Festival. I was not there, but I could see there are so many people writing about it. And I’m really looking forward to what they think here.

Q: With Masaan and Homebound, is there a trilogy in the making, considering the anti-caste subject you are exploring?

No, I mean, honestly. I want to make films that are of human emotions, of existential problems, social problems. Any of those, by keeping narrative at the fore. I’m a narrative filmmaker. That’s what I want to be known, that is my primary concern. It could, I may talk about caste. I may talk about village, and I may talk about sexuality, and we talk about feminism, identity. Many of these themes are of interest to me. And there is no conscious effort to make only films about caste. It just that nobody else is making it. You know, people don’t question the uppercaste privileged filmmakers who make only films about the uppercaste privilege who are lliterally 15% of the population. Nobody questions them. I come from a population of 25%. I’m literally the only person from the community. And I’m making a film, but people want to ask me, like, why you only making this.

Q: What are you writing now? What is your next project?

Nothing at all. I’m not a multitasker.

Q: How is the Oscar campaign for Homebound going for you and your team?

We are campaigning for the academy and the BAFTAs. It is a very, very competitive year this year, extremely competitive. A small film like ours is not spoken about much. I mean, let’s see what happens. Maybe the Oscar voters may like it. I’m not expecting anything. The campaign started in New York, where Martin Scorsese hosted a Q&A with me. Then we did a couple of screenings of Homebound in New York, and then we did a lot of screenings in Los Angeles for over a month. Then I did screenings in London. And after London, I’m here.