Late in February 2022, as Russian tanks rolled toward Kyiv, another drama was unfolding inside quiet offices lit only by the glow of compliance dashboards. Overnight, global banks froze billions in payments, auditors scrambled to rejig exposure maps, and shipping insurers cancelled coverage for hundreds of vessels. Within days, Russia’s central bank discovered that nearly half of its foreign exchange reserves were inaccessible.

No warning. No negotiations. Just a digital guillotine. No infrastructure was bombed. No soldier deployed. And yet, it was perhaps the most decisive economic strike since World War II.

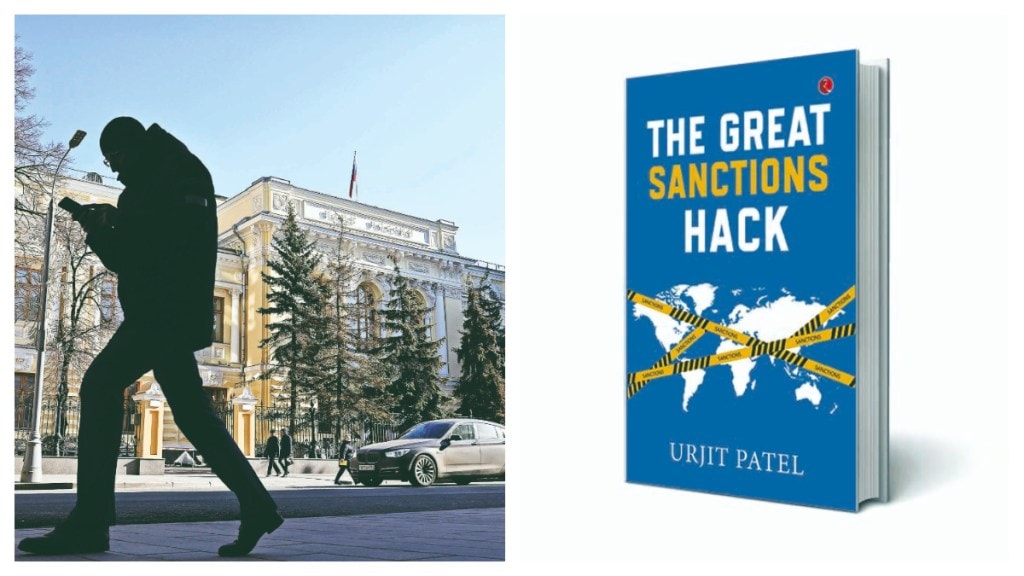

It is inside this shadow war that former Reserve Bank of India governor Urjit Patel situates his sharply argued book, The Great Sanctions Hack, a 145-page work that exposes how modern conflict has shifted from battlefields to balance sheets, and how the world’s financial wiring has become the battlefield of outrage.

Why Sanctions Are the New Siege

Patel writes that this moment marked a fundamental shift: economic sanctions were no longer symbolic punishments or diplomatic theatre — they had become a weapon with the destructive potential of war itself. Sanctions today, Patel argues in one of the book’s most memorable lines, are not amputation — they are asphyxiation.

And here lies Patel’s deepest insight: even when sanctions end, the damage doesn’t. Relationships don’t automatically reset; trust lost takes years to rebuild. He calls these sanctions ‘hysteresis’ — the shock that doesn’t fade even when the event does.

What turns sanctions from political gestures into instruments of strangulation is the architecture of global finance — the pipes and switches beneath the system. Patel maps this infrastructure with impressive clarity.

Patel is unsparing towards multilateral institutions — the IMF, World Bank, G20 — which he accuses of maintaining studied silence on sanctions’ global fallout. These bodies publish detailed research on tariffs, currency movements and banking crises, yet rarely measure sanctions’ humanitarian or developmental impact. Coming from someone who has been RBI governor and now represents India at the IMF, this critique carries considerable weight.

Sanctions, Patel argues, are treated as moral theatre by great powers — cleansing tools for political narratives. But the pain is borne far away and the suffering is silent, statistical, invisible.

De-dollarisation and India’s Tightrope

If sanctions are the new siege weapon, then the global move toward de-dollarisation is, in Patel’s telling, not rebellion but survival. Countries are not abandoning the dollar; they are hedging against vulnerability. For example, BRICS payment systems; local currency trading corridors; gold accumulation; Yuan settlements and regional clearing mechanisms. These are not ideological projects. They are insurance policies.

Patel’s warning is clear: the more the US weaponises the dollar system, the faster the world will work to reduce its dependence on it as power overplayed becomes power eroded.

For Indian readers, the most compelling sections analyse the tightrope India must walk in an era of sanctions-driven geopolitics. The Russia-Ukraine war made India a case study in agility: buying discounted Russian oil strengthened its macro-economy even as the West pushed for alignment.

Yet that opportunity comes with risk as Indian exporters now operate under compliance scrutiny; banks hesitate on dollar clearances involving sanctioned regions, and financial routes that were invisible are now exposed.

India is neither a sanctioning power nor a sanctioned economy — but it is deeply vulnerable to a world where access determines strength and exclusion determines fate. Patel suggests that economic autonomy in the 21st century will depend less on self-reliance slogans and more on diversified financial channels, resilient payment systems and geopolitical flexibility.

Patel writes without drama. His tone is measured, almost understated — the voice of a technocrat who believes facts should frighten us more than rhetoric will. And yet the drama of the book lies precisely in that restraint.

He forces the reader to imagine a world where economic war needs no military approval, no parliamentary vote, no public transparency. A world where a single compliance directive can decide whether a child lives or dies.

The Great Sanctions Hack is ultimately a book about power — who holds it, who feels it, and who never sees it coming. It is about a global financial system so concentrated that it can be weaponised with stunning speed, and about the moral cost of using invisible tools to achieve political ends.

It is a warning, a map and a mirror — showing a world drifting toward financial fragmentation without realising the danger. Sanctions may be silent. But, as Patel reminds us, their echoes shape destinies.

The book wears its author’s central-banker DNA on every page. Sanctions have exploded in use, but not in effectiveness, Patel argues. Drawing on global academic data, he points out that since 2000, fewer than one in five sanctions episodes have actually met their declared objectives — even as the number and scope of sanctions have multiplied. Yet he is not arguing that sanctions never work. Rather, his point is that the way we talk about and measure them is dangerously simplistic — binary success/failure judgments that ignore long lags, spillovers and collateral damage.

If there is a limitation, it lies not in clarity but in ambition. The book stops short of issuing a detailed policy blueprint for countries like India — for example, what a sanctions-proof payments ecosystem should concretely look like, or how emerging economies can collectively influence global governance reform. Readers seeking a prescriptive toolkit may find the conclusions high level.

Patel is clear on the costs, distortions and overuse of sanctions. Less clear is his explicit normative stance on when sanctions are justified, or what a ‘better’ global regime would look like beyond more transparency and better metrics. Some readers may want stronger prescriptions.

Finally, the technical tone, while precise, may feel emotionally distant. There are few human stories or frontline narratives; this is primarily a policy economist’s book. Despite his efforts at simplification, a reader with no background in macro, trade or finance might find it heavy going.