By Mitali Nikore

By now, it is well-known that India’s female workforce participation rate (FWPR) remains amongst the lowest globally. In 2019-20, just about 30% of working-age women were in the labour force. Even amongst the highly educated, the workforce participation is low. The FWPR amongst graduates is only 24%, and rises to 38% for postgraduates – implying that nearly 60% of highly educated women are not at work in India.

COVID-19 has worsened this gender skewness further. As the dust settles on the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, the composition of India’s labour force looks very different in January 2022, compared to just two years ago. Women’s representation in the labour force has contracted, particularly in urban areas.

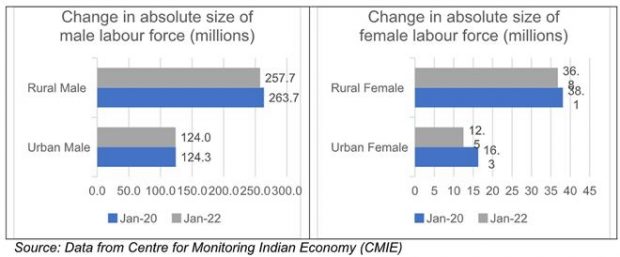

Overall, between January 2020 to January 2022, the labour force has contracted by about 11.3 million, 5.1 million women and 6.2 million men (as per CMIE data). However, while women’s labour force is 9.4% smaller, the contraction is only 1.6% for men. Most notably, about 3/4 th of the reduction was driven by the fall in urban women’s labour force participation.

Not only are fewer women returning to the workforce post COVID-19, but they are also more stressed, and have lower productivity owing to a greater burden of unpaid care work. In consultations undertaken by Nikore Associates between August 2020 to December 2021, nearly every female respondent, be it a start-up founder, or a corporate employee mentioned an increase in carework, owing to school closures and imbalanced expectations of shared domestic responsibility between spouses. While some reported being thankful for the increased flexibility owing to the “work-from-home (WFH)” model, others felt it deterred delinking office work and unpaid work. Surveys by Avtar Inc. directly corroborate our findings, where the analysis reveals that 96% of men spent below 3 hours on housework, while 85% of women spent between 2-5 hours daily.

Nikore Associates’ consultations also revealed that the lack of institutional support systems from companies was a key deterrent towards returning to work for women, especially for full-time, in-person job roles. Surveys by Deloitte show that over 63% of women employees felt their work was judged by time spent online than the quality of the output, only 39% felt supported by their organisations during COVID-19 and 23% reported considering leaving owing to the work stress.

This raises a key conundrum for India Inc. – despite a consistent increase in the number of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives, gaps persist between intended and actual impact on employee satisfaction, productivity, retention and growth.

In order to deep dive into these gaps, Nikore Associates undertook an analysis of over 500 DEI initiatives implemented by Nifty50 companies in the last two years of the pandemic as a case study. This analysis has shown that DEI initiatives are clustered into 4 major categories – maternity benefits (96%), prevention of sexual harassment (100%), mentoring for senior leadership (80%), and diversity hiring policies (94%) with 76% of Nifty50 companies implementing all four of these “traditional” DEI initiatives. It can also be observed that a large proportion of these actions ensure statutory compliance, such as the six-month maternity leave (Maternity Benefits Act, 2017) and setting up the internal complaints committees (Prevention of Sexual Harassment Act, 2013).

Encouragingly, there are some early traces of innovation in DEI initiatives such as gender sensitisation trainings to address cultural, social, and unconscious biases being offered by 16% of companies; efforts for women to undertake non-traditional job roles being by 6% of companies; and peer support networks for women employees (12%) and young parents (6%). However, these are only offered by small sub-section of companies.

On the other hand, while there has been an increase in childcare and creche facilities at the office (38%), programs encouraging women to return to work post career breaks (36%), gender-neutral parental leaves (36%), only few companies offer paternity leaves, flexible work hours for care-work or tailored programs for retention of women employees.

This exodus of women from the urban sector labour force, juxtaposed with an already low urban FWPR even amongst educated women is indicative of missed opportunities to attract women’s talent to India Inc. Moreover, worsening mental health, the burden of unpaid work, and continuing gaps between the actual and intended impact of DEI initiatives suggest that corporates need to re-examine their DEI priorities, in line with the following key principles that are described in more detail in the Nikore Associates Gender Primer on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion:

Principle no. 1: Listen to employees, especially women. Adopt a bottom-up culture, run pilots, and ask the employees, especially women to speak-up, participate in open forums, and respond to anonymous surveys to pinpoint the exact gaps in existing policies, and understand employee needs.

Principle no. 2: Data-driven DEI. Regular data collection to track diversity metrics, representation of women at different seniority levels and departments, can help companies measure and assess effectiveness and impact of DEI initiatives.

Principle no. 3: Lifecycle approach. A comprehensive DEI strategy does not take a piecemeal approach, and rather focusses on the lifecycle of the employee from hiring to retention, and then to growth and professional development. This can help in creating a pipeline of women at different stages of seniority in the organisation.

Principle 4: Five stage gender-inclusivity framework for implementation. Companies can follow a 5-stage gender-inclusivity action framework, starting with a baseline analysis to benchmark company performance across key metrics of gender equity, then move to the analysis of alternative policy options, and then to actually implementing priority policies to maximise value for money and policy effectiveness. The final stage is impact evaluation, which is essential to understanding whether the selected policies were able to deliver on their targets and intended impact.

Research Advisor: Kirandeep Virdi

Research assistance: Laboni Singh, Avantika, Sanaa Chawla, Divyanshika Pandey, Mehak Vohra, Riya Kalia

Note: This article focusses on the current situation of under-representation of women in the workforce. As Indian companies and DEI policies evolve, the meaning of diversity will extend beyond women’s representation to include gender minorities, and eventually to include several under-represented social groups.

(The author is Founder, Nikore Associates. Views are personal)